Essential Art and the New World Order

RISING’s artistic associate Kimberley Moulton reflects on essential First Peoples art.

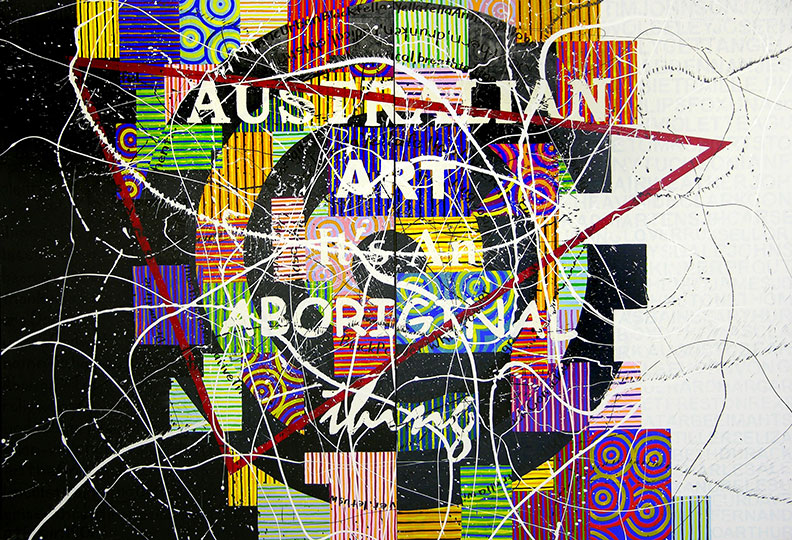

RICHARD BELL, AUSTRALIAN ART, IT’S AN ABORIGINAL THING, 2006. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MILANI GALLERY, BRISBANE. TARRAWARRA MUSEUM OF ART COLLECTION

"Globalization and conceptions of a new world order represent different sorts of challenges for Indigenous peoples. While being on the margins of the world has had dire consequences, being incorporated within the world’s marketplace has different implications and in turn requires the mounting of new forms of resistance."—Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples

“Essential” is a defining word of 2020. Since COVID-19 hit Australia earlier this year we’ve been asked to assess what’s essential for our survival; what’s an essential reason to leave home; what’s the essential infrastructure for safe commuting and social interactions. We’ve also been asked to permit essential testing of our bodies and allow essential development of regional landscapes and our Ancient ecologies. For many, this last point, means a non-essential destruction of Country and disrespect of First Peoples.

As we come to understand and control COVID-19, at least in Australia, we continue to battle the enduring disease of racism in society. A pill of denial has been swallowed by powerful factions across the world who, in a collapsing world, refuse to quell the rise of white supremacy and disastrous climate change. People of Colour and First Nations peoples are feeling the full force of this toxic fire fuelled by greed, power and narcissistic charlatans masquerading as leaders.

In our new world we’ve had to consider what’s needed to survive and what must change. Art in diverse forms has saved us this year. Author Benjamin Law summed it up well: “In our most dire hours, art keeps us sane, lights the dark and ensures we stay human”.

It’s through art that we can communicate and explore which actions are vital for the continuation of humanity–actions that go beyond how many toilet rolls we need. I would argue that First Peoples artists, and other communities that have historically been on the margins from the “white centre”, have always made art about what is essential.

In Australia this lineage stretches from the very first Ancestor artists who painted and engraved designs of Country, seasons and kin connections on cultural objects and rock sites, to movements of painting and new media in the regions and the city.

First Peoples art has always been about continuance, resistance, survival and celebrating all that is strong in our cultures, particularly given that this is not our first pandemic. In 2011 the prolific Australian artist and Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman and Gurang Gurang man Richard Bell said: “I’m an activist masquerading as an artist”1. The political entwined in art and identity is a common thread across First Peoples’ artistic practice.

This is largely because in a world where we continue to have to fight for representation, for sacred sites on Country, and for identity, our existence is inherently political. It is not to say that all First Peoples in the arts should, or do, make political work, but for many decades, art has been the vessel for essential action and awareness, and it will continue to be.

Two years ago, the New York Times ran the article ‘What Do We Mean When We Call Art Necessary’ that critically looked at the ideology of “necessary art” being widely used by critics, and suggested that descriptor “constrains more than it celebrates” particularly when it comes to marginalised peoples. The author argued that: “What has become truly necessary is stating the obvious: No work of art, no matter how incisive, beautiful, uncomfortable or representative, needs to exist”. This statement does not consider Indigenous experiences of art making and the multiple layers of politics, self-determination and representation of culture that are, in fact, absolutely necessary.

Now more than ever, it is time to consider how art is crucial to all of us for our health and the empowerment of marginalised peoples. It is also important to reflect on what defines essential art. I have until recently considered it a privilege to be completely neutral in contemporary art making. However, in the “new world order” (that Linda Tuhiwai Smith speaks of, not the conspiracy theory), if you have a platform, to abscond from addressing the world’s diverse realities and intersecting issues is to perpetuate major inequities. Neutrality is a myth and First Peoples do not have the luxury of tapping out of reality in our art making.

In her essay for the 2018 exhibition Sovereignty at Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Wemba Wemba and Gunditjmara artist and academic Paola Balla said: “First Nations artists awaken a sense of responsibility rarely seen in settler art or curatorial work. There is a collective consciousness and obligation, to make work that is, as Toni Morrison wrote ‘at its thrust, yes political but also irrevocably beautiful’”.2

Our voice and our art, in all of their beauty and politics, are essential—now.

RICHARD BELL, AUSTRALIAN ART, IT’S AN ABORIGINAL THING, 2006. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND MILANI GALLERY, BRISBANE. TARRAWARRA MUSEUM OF ART COLLECTION

REFERENCES:

1 Richard Bell in conversation with Rex Butler, James C. Sourris Artists Interview Series, State Library of Queensland 2011 and as quoted in Decolonising Now: The Activism of Richard Bell by Daniel Browning 2013.

2 Balla, P. Sovereignty: Inalienable and intimate in Sovereignty, exhibition catalogue ACCA 2017. Curators Paola Balla and Max Delany.